The removal of Te Tiriti o Waitangi from Section 127 of the Education and Training Act also spills over into strategic plans. For the uninitiated, school strategic plans are how a school board translates the high level legislative direction to boards found in Section 127 into something that is meaningful for their community. This localising of the Act is desirable. It is how boards answer the How are WE going to make this real HERE, for OUR kids? question.

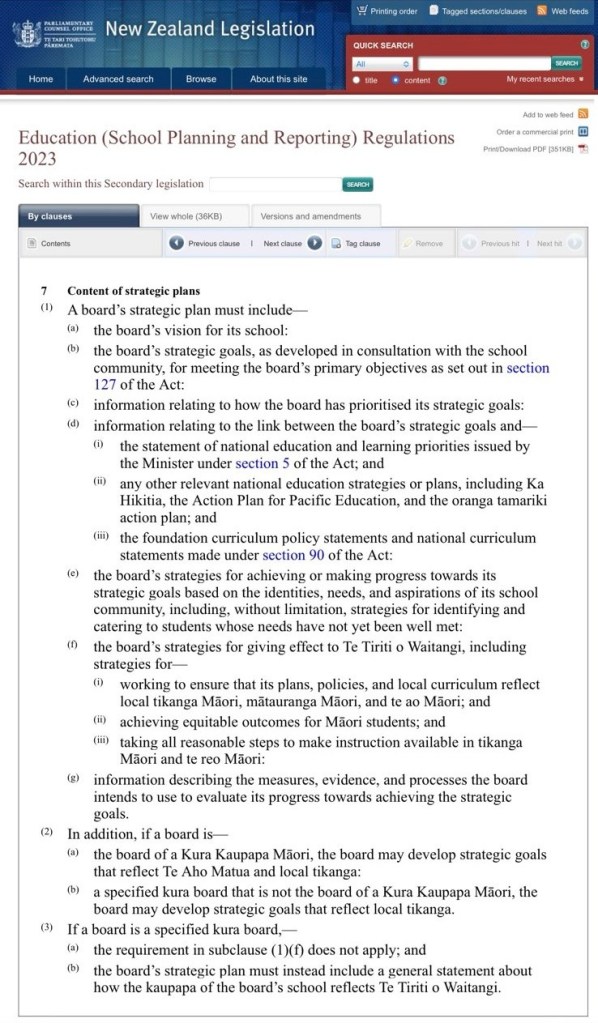

The legislation says that strategic plans must contain the following.

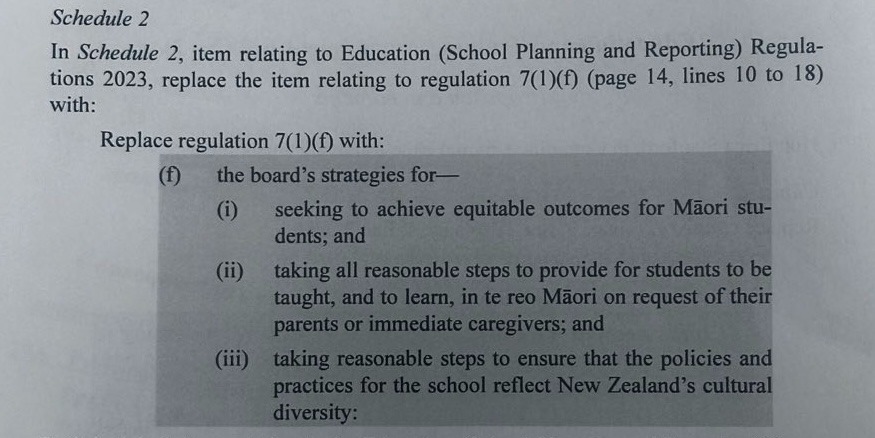

This section is about to undergo significant change. Section 5 (which is where the three objectives of the system are stated as being of equal importance) is being removed from the Act, so it will no longer be required in new strategic plans. Furthermore, in 7(1)(f) reference to Te Tiriti o Waitangi is being removed, in line with its removal from Section 127, and it is now simply “board strategies for”. We also see a significant shift in the way this part is defined.

It is worth considering the impact of these changes, for they herald a complete reframing by this Government of how Te Tiriti and its obligations are being conceptualised in education. Since its inclusion in the Act, 7(1)(f)(i) has meant that Māori have had their right to be a voice at the table, working in partnership with the school, baked into a board’s legislative requirements. In practical terms, this means that Te Tiriti’s principles – Partnership, Participation, Protection – have resulted in schools actively including Māori. Wondering what that looks like? Think of the increasing visibility of Te Ao Māori in schools through things like pōwhiri, kapa haka, te reo, noho marae, pūrākau, field trips. Think of how that increase has helped create a more welcoming, inclusive culture for everyone in schools.

Minister Stanford’s justification is that this work is too complex and vague for boards, which are, in her words, composed of volunteers, a word no doubt carefully chosen to diminish their status as elected representatives with expertise. Accordingly, she argues, it is reasonable for the Government to relieve them of their Treaty responsibilities and assume it themselves.

But boards are still Crown agencies and so carry the authority and responsibilities of the Crown. With regards to local government, The Waitangi Tribunal found that when the Crown delegates its authority it must do so in a way which ensures its responsibility to the Treaty, specifically the duty of Protection under Article 2, is able to be fulfilled.* This is a similar situation. Here, Minister Stanford is seeking to reduce the scope of board Te Tiriti responsibilities to being little more than enactors of the Government’s education policies. She wants us to read board adherence to those policies as them fulfilling their Te Tiriti obligations. But this will undermine their ability to meet their duties in relation to Article 2. This is delegation of authority without responsibility, a position The Waitangi Tribunal found unjustifiable in relation to local government.

For with the erasure of Te Tiriti, and the corresponding disappearance of its principles, we also have the arrival of a unilateral definition on behalf of the Government of what upholding Te Tiriti means. The amendments in this section to do with board strategic planning spell out this definition: a school is now upholding its Te Tiriti obligations by offering little more than the opportunity for academic achievement in a European context, with the what and how of that opportunity tightly defined and enforced by a highly prescribed curriculum. As Willow-Jean Prime asked Minister Stanford in the debate, Who gave her the right to decide this? Who did she ask for permission to make that decision?

Let’s be real: this erasure of Te Tiriti from board objectives and their strategic planning means there is now no legal obligation for schools to partner with Māori. David Seymour says this is about choice; we all know what happens when those with power get to choose who they listen to.

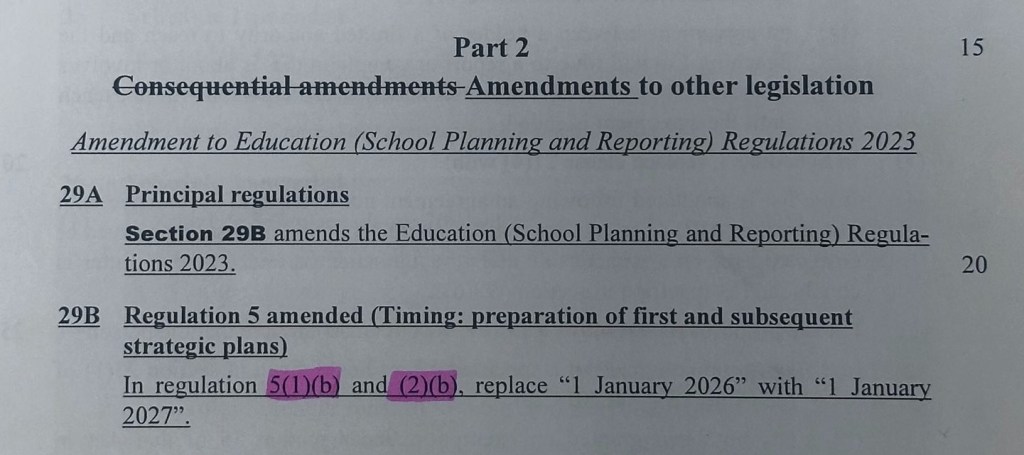

But there is a glimmer of hope. The select committee report, prepared before the last minute amendment that removed Te Tiriti from these sections, recommended the date for the adoption of new strategic plans be moved out a year, until 2027. Erica Stanford accepted this recommendation. In the debate, Willow-Jean Prime pointed out that this meant boards got a another year to operate under their existing (Te Tiriti-infused) strategic plans.

Because you are able to operate with your existing strategic plan for another year, you have a legal way to delay the effects (adoption?) of these legislative changes.

For a year longer than Minister Stanford wanted, Te Tiriti is legally alive in your school. All you have to do is not change your plan.

Take that opportunity. A lot can change in a year.

* The Manukau Report (1985) and the Ngawha Geothermal Resources Report (1993) are cited as the leading statements regarding local government obligations under the Treaty.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

Leave a comment