And the problem Aotearoa New Zealand now has

A short primer on why I am concerned

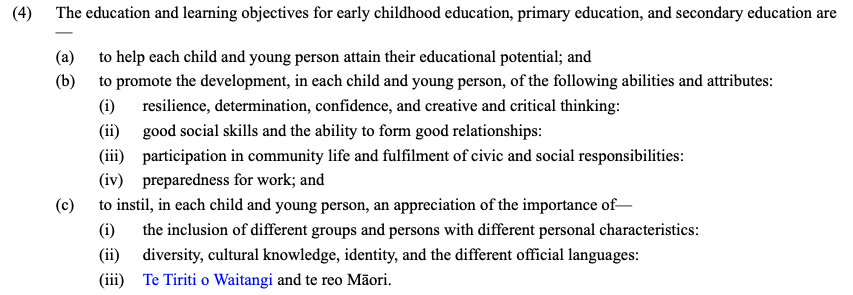

The basis of our curriculum is the Education and Training Act. In that act, section 5 (4) sets out the education and learning objectives for schools, of which there are three. Key things to note about these objectives:

- each learner has a right to academic achievement

- the development of more ‘dispositional’ skills and abilities are to be promoted

- schools have to be inclusive places where te reo Māori and Te Tiriti are important.

One might say that (b) and (c) are objectives the legislation has to ensure the education system develops things that are beyond knowledge and academic achievement, yet are just as important when it comes to developing as a person. So, we have a legislative basis for the claim that schools are results PLUS places. This is not just a hopeful claim made by those who put themselves in the progressive education pot, it is a legal requirement.

It is worth pointing out that there is no hierarchy here, no primary objective identified. Therefore, the only inference we can make is that all three objectives must be given equal attention in a school. Given the curriculum creates the regulatory framework for how the act is to be brought to life or realised in a school, we should expect to see this balance reflected in that document.

The curriculum refresh process up until mid-2023, which resulted in the near completion of Te Mātaiaho, showed a clear attempt to bring those three objectives into balance. Te Tiriti was given a foundational place in the document. The conceptual underpinning of the curriculum phases, the unpacking of the essential pedagogies, and the Understand-Know-Do framework were ways in which objectives (b) and (c) were integrated into the work of schools.

But something significant has changed since early 2024. Not only is the content of the curriculum different, we have witnessed a contrasting approach to the curriculum’s legislative basis. The highly detailed, highly prescriptive, deterministic, ‘knowledge-rich’ nature of the draft curriculum documents, which are being produced as a result of the recommendations of the Ministerial Advisory Group1, act to make academic progress and achievement the unmistakeable focus of schools. In essence, (a) becomes the primary objective, despite the legislation making no such distinction. This is creating problems for schools and teachers — how are they to give (b) and (c) the attention the legislation requires? And this is a problem for our democratic foundations — is it really the case that a curriculum can implicitly prioritise one of the three objectives when the legislation does not?

The machinations of how this has occurred is the current focus of my research, and will form the basis of my next report.

- We know the makeup of this group was hardly representative. See my first report if you missed it for more information about that. ↩︎

One response

[…] Also proposed to be removed is section 5, which contains within it the requirement for consultation when it comes to curriculum development, as well as the education learning objectives. I wrote about the implications of this in April. You can read that here. […]