What must education look like in a world that’s on the precipice?

It’s a question that’s made me think about what it really means to provide a future-focused education. What I often hear schools talk about when the phrase is used is digital technology. In a way, they’re not wrong—tech ain’t going anywhere & kids will need to be au fait with it. However, it’s a response that I think misses the broader point, & in doing so falls into the trap of serving the interests of an economic paradigm that has got us close to the edge. Being future-focused must mean more than making sure kids know how to use tech so they can get jobs.

Look at the world at large. All around us we see social & environmental collapse & destruction. Nowhere is immune. And the solutions, if we can call them that, are not going to be found in a magical tech-utopia so often preached to us. This is not a story where the world is saved by a hero whose genius is scaled by venture capital.

So, what will give the kids a shot in this future? Perhaps if we start with considering the cognitive foundation for how we learn. Mary-Helen Immordino-Yang, a professor of education, psychology & neuroscience at USC, makes this important point:

“It is literally neurobiologically impossible to think deeply about things that you don’t care about. … When students are emotionally engaged … we see activations all around the cortex, in regions involved in cognition, memory and meaning-making, and even all the way down into the brain stem.”

— from the article, ‘To Help Students Learn, Engage the Emotions.’

It’s a simple, yet profound statement. It’s true for me, & I’m confident it’s true for you too: I cannot think deeply about something I do not care about. This gives us a pointer as to where we need to start if we’re going to be truly future-focused: with care at the heart of education, because being able to think deeply about the world around us is going to become crucial in helping us to understand what’s happening to the world around us & what we should do.

But how? Care, as Alison Pouliot reminds us, is “difficult to articulate”. Compounding that is the fact that it can be easy to offer care in a glib, superficial way. As Pouliot says, care

“… is not an attachment, an afterthought or an overlay on rational understanding. It is not a box to be ticked, but a genuinely & deeply felt sense. I think about how care is more important than data.”

So where does this leave us? In chewing this idea over, I’ve been thinking about another context in which care is essential—the regeneration of ecosystems—where attention & curiosity, hand-in-hand with documentation, helps those responsible think deeply about what is required to bring life & vitality back. Kazuko Yamamoto describes what’s required:

“Keep noticing, responding, connecting deeply, giving, loving. But maintain rage. It’s all part of caring.”

Isn’t that interesting: she includes rage as part of caring. Perhaps it’s because for regenerative work to be required, there must have been harm done. When it comes to ecosystems, the harm is often easy to spot: landscapes scraped dry, denuded, polluted. We can spot people who have been harmed too, sometimes. For us, is it worth thinking precisely about how an education system harms the people in it, often quietly, sometimes loudly? Would harnessing that rage help us? I think so. But we must be careful with how we hold it.

Here’s what I think. At heart, the problem we have is one of disconnection. So many of our environments are sanitised now, & our freedom to move within them is constrained. This includes schools. On the whole, kids’ lives consist of whizzing from one constrained, sanitised environment to the next. But while this might be an efficient way to provide our kids with a wide range of opportunities for them to ‘meet their potential’, there are some subterranean, secondary-effects that are problematic.

Sanitised places make it hard to be curious. With their reduction in diversity, there are fewer opportunities to awed, stumped, challenged or enthused. The accidental fades from view, replaced by the intended … predictable … safe … trivial.

When we whizz, we have no time to see, & seeing is the first step toward thinking. Thinking is a meandering, time-hungry process that cannot be rushed if it is to be deep: it relies on the unexpected pause; it is intimately linked with curiosity. Taking time to see & think tunes us into nuance & complexity, expanding our capacity to be amazed.

Only when we care, as Immordino-Yang reminds us, are we able to think deeply. And in a world on the precipice, we really need to care about our world. That means we need to be as connected to it as possible. I think that means schools need to facilitate that closeness.

Sally Weintrobe writes deeply about what she calls the ‘culture of uncare’. She argues it is a design feature of neoliberalism, where economic growth is privileged above all else, yet is dependent on disconnected thinking & the deliberate unseeing of hidden interconnections & relationships. The culture of uncare, Weintrobe writes, relies on a failure of imagination to envisage any other way to be.

A world that is on the precipice is going to need people who have learned to pay attention to the complex, nuanced relationships around them; people who know & care for place, allowing them to think deeply about it. We are going to need people with the imagination to see ways of being in the world beyond economic gain. In many ways, this is a form of literacy & we need to get as worked up about it as we do about how well kids perform on reading tests.

We can turn the needle on this by putting care at the heart of learning in schools—fostering curiosity is a way we can do that. Curiosity is an attention driver, helping us zero in, follow our nose, ask questions. It is the bridge between our senses & our conscious mind. And the good news is, it’s not hard to nurture. There are questions we can ask when we talk with our learners, experiences we can offer them, & small tweaks we can make to how we present opportunities to learn, that will help nurture the growth of our learners’ curiosity.

As I was diving into my thinking about this, I turned to books—those devices where deep ideas are found. One of those books was a collection of essays by Margaret Atwood (Burning Questions) & in it an essay called ‘We Are Double-Plus Unfree’ spoke to me. In it she draws at distinction between “freedom from” & “freedom to”, saying

“… our “freedom to” is limited to approved & supervised activities, & our “freedom from” doesn’t keep us free from the great many things that can end up killing us … Freedom from toxic chemicals in the air & water? Freedom from floods, droughts & famines? Freedom from defective automobiles? Freedom from the badly prescribed drugs that are killing hundreds of thousands of people a year? Don’t hold your breath.”

It’s worth thinking about how care can be a path toward a different kind of “freedom to”. For to care means to be curious; do hard but necessary things; think deeply; imagine a better world; connect deeply; have confidence to act meaningfully, responsively, & do our best to do what’s good & right.

It means to love. It means to rage against the things that harm us.

Any parent would want their child to approach the world with these positive dispositions. The writers of our curriculum documents know this, & know they’re important, which is why you can find variations of these dispositions in them. The problem is, when they’re deeply engaged with they tend to lead away from the techno-utopian future dreamed up for us by those who profit from disconnection & the culture of uncare.

We don’t have to accept that uncaring, techno-utopian dream. We can use our classrooms as spaces of rebellion against it.

It’s time to start getting our hands dirty by creating space for curiosity.

Interested in the tweaks that grow curiosity?

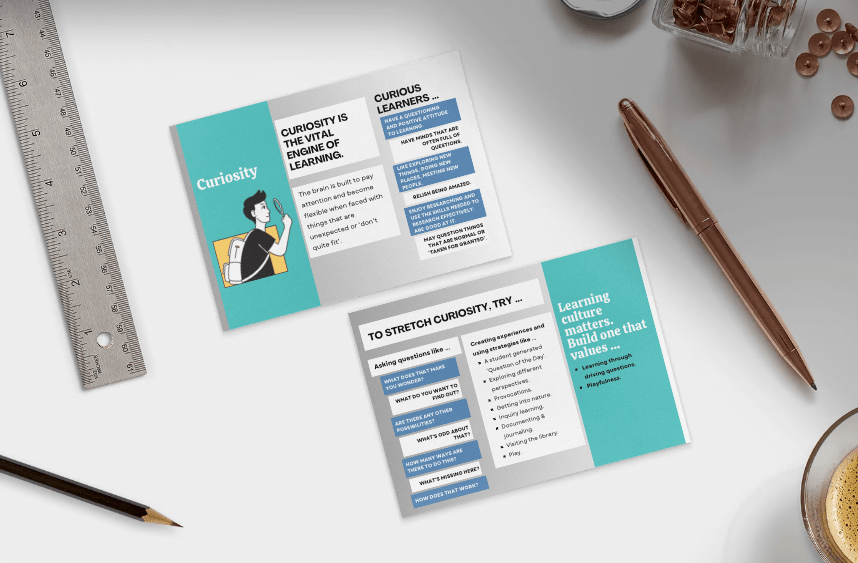

Guy Claxton, Becky Carlzon & I have spent time developing a framework that will help all teachers nurture a set of positive dispositions that will help all kids become powerful learners.

Soon, we will have available for sale cards with some simple, practical tips & tweaks you can use to notice, recognise, & respond to the growth of the seven dispositions in our framework: curiosity, persistence, imagination, attention, thinking, communication & collaboration, craftsmanship.

You can register your interest by completing this form.

Your message has been sent

Thanks for reading 🙂

If you received this post via email, it’s because you were subscribed to my Substack, The Idiosyncratic Classroom. I have left Substack because of their stance regarding supporting & profiting from Nazi content. This is the new home for my writing.

If you’d rather not receive these posts as emails, feel free to unsubscribe.

But, if you liked this post, feel free to share it.

4 responses

Thanks Bevan, I really enjoyed this and the focus on observing and responding to children. And I agree that when they care deeply and it matters their responses are so much more meaningful.

Thanks Deb. Yes, much more meaningful. Surely that’s what we want!

Hi, Bevan –

Thanks for this excellent post. I can sign on to rage as part of care!

We just completed a month’s focus on care at our Studio (www.storyworkshop.studio). As part of it, we had a conversation with Junlei Li, who talked about how rarely care is explicitly discussed in the research. His commitment as a scholar who regularly goes into spaces and creates frameworks is to focus on what caregivers are doing right rather than focus on critique. Interestingly, he also refuses to use the language of “child centered” approaches – he emphasizes “relationship-based” because he thinks we need to include care for the care giver.

And, re Mary Helen Immordino-Yang: Did you hear this fantastic conversation https://soundcloud.com/rethinking-ed-podcast/re25-mary-helen-immordino-yang? Her call for a “Copernican revolution in education” seems right in line with your work.

Happy new year! Here’s to centering care in 2024!

Matt

Ooohh – Junlei’s work sounds fantastic. I must say, I can see why he refuses to use child centred & I’m pleased what he uses instead. Really, that’s the true meaning when you think about it.

Thanks for the link. I’ll enjoy listening to that. I really do like her work.

Happy New Year to you too!